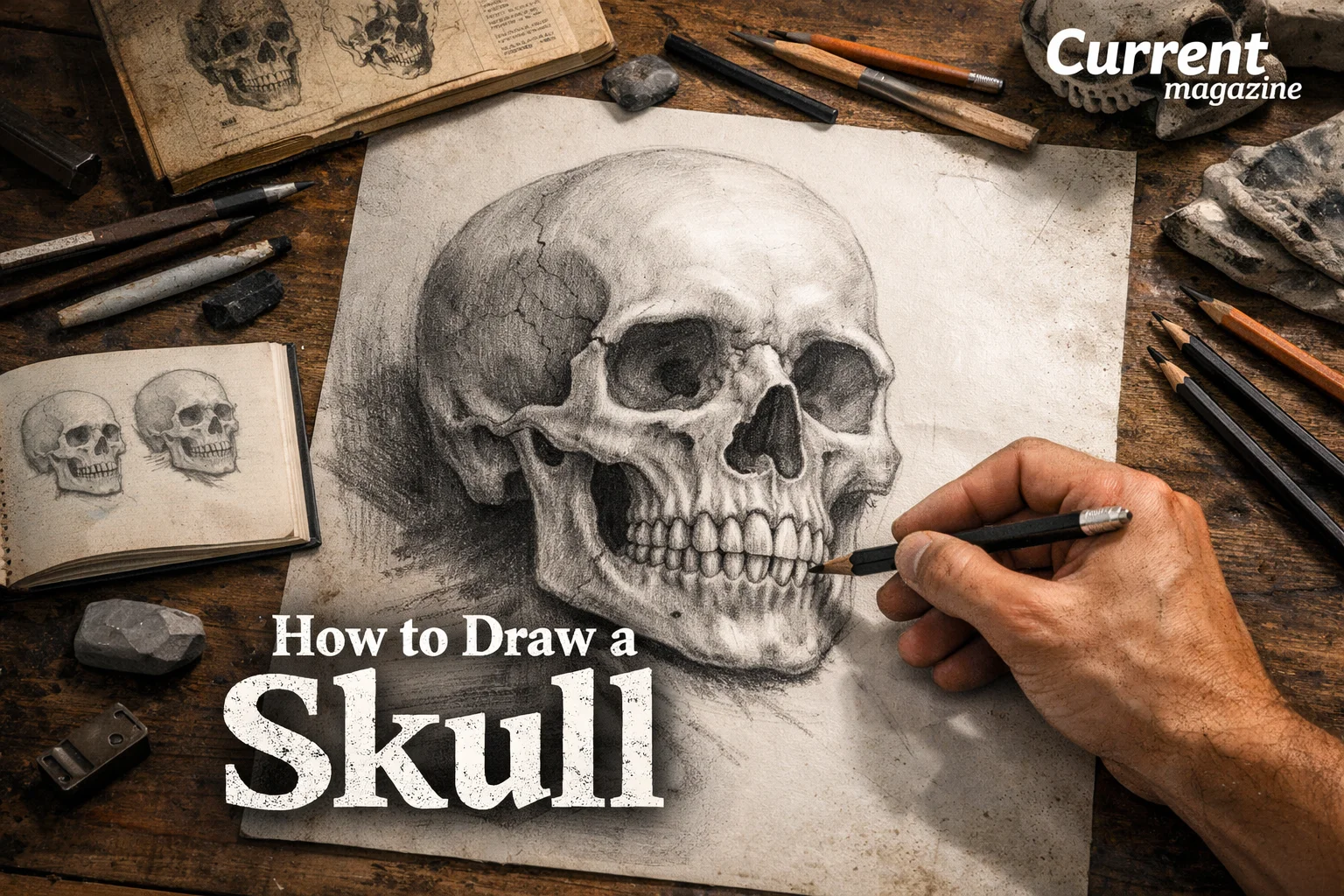

Learning how to draw a skull is an essential skill for any artist interested in anatomy, illustration, or creating compelling artwork. Whether you’re a complete beginner or looking to refine your technique, drawing skulls helps you understand facial structure, proportions, and shading. Skulls appear in everything from medical illustrations to tattoo designs, comic books to fine art. This detailed guide will walk you through the process of drawing a realistic skull from start to finish, breaking down what seems complex into simple, manageable steps.

Why Learn to Draw Skulls?

Before we dive into the actual drawing process, it’s worth understanding why skull drawing is such a valuable exercise for artists.

Skulls are the foundation of facial structure. When you understand how to draw a skull, you automatically improve your ability to draw faces. The skull determines where eyes sit, how the nose projects, and the shape of the jawline. Portrait artists often sketch the skull structure first before adding flesh and features.

Drawing skulls also teaches you about three-dimensional form. The skull has curves, planes, and hollows that challenge you to think beyond flat shapes. You’ll learn how light interacts with rounded and angular surfaces, which translates to drawing almost anything.

Additionally, skulls are fascinating subjects that appear across cultures and art movements. From Day of the Dead celebrations to heavy metal album covers, from Renaissance paintings to modern street art, the skull remains a powerful and popular image.

Materials You’ll Need

You don’t need expensive supplies to start drawing skulls. Here’s what will help you get started:

A regular pencil (HB or 2B) works perfectly for sketching and general drawing. If you want to explore shading more deeply, having a range of pencils from hard (2H) to soft (6B) gives you more options for light and dark values.

Any drawing paper will work, though slightly heavier paper (around 70-90 lb) handles erasing and shading better than thin notebook paper. As you progress, you might enjoy smoother paper for detailed work or textured paper for more expressive sketches.

A good eraser is essential. A kneaded eraser is fantastic because you can shape it to lift graphite from small areas, but a regular pink or white eraser works fine too.

Optional but helpful items include a blending stump or tortillon for smooth shading, a ruler for checking proportions, and reference images of real skulls. Looking at photographs or, ideally, actual skull models helps tremendously.

Understanding Basic Skull Anatomy

Before putting pencil to paper, familiarize yourself with the skull’s basic structure. You don’t need to memorize every bone name, but understanding the major features helps your drawing look convincing.

The skull consists of two main parts: the cranium (the rounded brain case on top) and the facial bones. The cranium is roughly oval-shaped and makes up about two-thirds of the total skull height.

Key features to notice include the eye sockets (orbits), which are large, rounded openings positioned in the upper-middle of the face. The nasal cavity sits below and between the eye sockets, shaped like an upside-down heart or pear. The cheekbones (zygomatic bones) arc out from the sides, creating the widest point of the skull. The upper and lower jaws hold the teeth, with the upper jaw fixed and the lower jaw separate.

The temporal area (sides of the skull) has a shallow depression where the jaw connects. The forehead slopes back slightly from the brow ridge, which is a subtle bump above the eye sockets.

Step 1: Drawing the Basic Shape

Start with simple shapes to establish the overall proportions and structure. This foundation makes everything else easier.

Draw a circle for the cranium. Don’t worry about making it perfect—skulls aren’t perfectly round anyway. This circle represents the brain case and should take up about the upper two-thirds of your final skull.

Below the circle, draw a smaller rounded shape for the jaw area. Think of it like a rounded rectangle or a squared-off oval. This shape should be about half the width of your circle and extend down about one-third the height of the circle.

Connect these shapes with gentle curved lines on each side. These lines represent the cheekbones and sides of the skull. The overall shape should now look like a rounded head with a narrower bottom.

Draw a vertical centerline down the middle of your skull shape. Then add a horizontal line about halfway down the circle. This horizontal line marks roughly where the eye sockets will go. Add another horizontal line where the circle meets the jaw shape—this guides where the bottom of the nasal cavity sits.

Step 2: Placing the Eye Sockets

Eye sockets are one of the most distinctive features of a skull, so getting them right makes a huge difference.

The eye sockets should sit on or just below that horizontal guideline you drew. Each socket is roughly circular but slightly taller than it is wide. The inner edges of the sockets should align roughly with the width of the nasal cavity, while the outer edges sit about where your side guidelines are.

Draw two large circles or ovals for the sockets. Make sure they’re evenly spaced on either side of your centerline. Each socket should be about one eye-width apart from the other (meaning if you drew another eye socket between them, it would fit comfortably).

The sockets aren’t just flat circles—they’re deep cavities. Indicate this depth by darkening the areas, especially the top and inner portions. The top of each socket has a subtle shelf created by the brow ridge.

Inside each socket, you might notice in real skulls there are small openings and textures. For a basic drawing, you can suggest this with some light shading that gets darker toward the back of the socket, creating that hollow appearance.

Step 3: Adding the Nasal Cavity

The nasal opening is simpler than it might seem at first glance.

Starting at the horizontal line between your circle and jaw shape, draw an upside-down heart or pear shape in the center of the skull. The top of this shape should be narrower, widening as it goes down, then narrowing again slightly at the bottom.

The nasal cavity sits between and slightly below the eye sockets. Its top edge should be roughly level with the bottom edge of the eye sockets, though this varies slightly between skulls.

Inside the nasal opening, there’s a vertical dividing structure called the nasal spine. Draw a small vertical line or narrow triangle shape coming down from the top center of the nasal cavity. This doesn’t extend all the way down—maybe just a third or half the height of the opening.

The bottom edge of the nasal cavity often has a slightly jagged or uneven appearance where the bone ends. You can indicate this with small irregular bumps or simply leave it as a curved line.

Step 4: Drawing the Teeth and Jaw

Teeth give skulls their distinctive character, but they can be intimidating to draw. Break them down into simple shapes.

Draw a curved horizontal line across the middle of your jaw area. This represents where the upper and lower teeth meet. The line should curve slightly, following the rounded shape of the jaw.

For the upper teeth, draw small rectangular shapes along the top of this line. Adults have 16 upper teeth visible from the front view (though you’ll see fewer from certain angles). The front teeth are slightly larger and more prominent. As teeth go back toward the sides, they get smaller and may disappear from view depending on your angle.

Draw small vertical lines between the teeth to separate them. Keep these simple—you don’t need to draw every detail of each tooth. The front four teeth (two on each side of center) are typically larger and more squared off. The teeth further back are smaller and more rounded.

For the lower jaw, repeat the process below the center line. The lower jaw is slightly narrower than the upper, so the teeth should follow a tighter curve.

The lower jaw connects to the skull at the temporal mandibular joint, located on each side near where the cheekbones end. Indicate this connection with a curved line or slight indentation on each side.

Step 5: Defining the Cheekbones and Structure

The cheekbones create the skull’s width and define its character.

From each eye socket, draw a curved line that arcs outward and down toward the jaw. This line represents the zygomatic arch (cheekbone). The cheekbones are typically the widest point of the skull, extending beyond the cranium’s sides.

These bones have a subtle three-dimensional quality. They’re not just flat arcs but rounded structures. Indicate this with light shading along the underside of the cheekbone, suggesting shadow beneath.

The temporal area (the side of the skull between the eye socket and the ear opening) has a slight depression. This area is slightly hollow compared to the rounded cranium above and the cheekbones below. You can suggest this with subtle shading or simply by showing how the contours change.

If you’re drawing a three-quarter view or side view, the cheekbone becomes more prominent and creates an important profile line. The bone projects forward from the side of the skull, creating depth.

Step 6: Refining the Cranium

The top and back of the skull have their own character and shouldn’t be neglected.

The forehead slopes back gently from the brow ridge. It’s not perfectly vertical but angles back at maybe 10-15 degrees. This slope continues up and over the top of the skull.

The back of the skull has a rounded, somewhat bulbous quality. It projects backward, creating the overall egg-like shape of the cranium. The very back might have a slight bump or protrusion called the occipital bone.

Where the jaw meets the cranium on the sides, there’s often a visible line or ridge. This area also has small openings (like the ear canal opening) that you can indicate with small dark marks if you want more detail.

Clean up your initial construction lines. Darken the final contours of the skull while erasing the guidelines you used for proportion. The skull’s outline shouldn’t be a uniform dark line everywhere—vary the line weight to suggest depth and form.

Step 7: Adding Shading and Depth

Shading transforms your line drawing into a three-dimensional form. This is where your skull really comes to life.

Determine your light source first. Decide where light is hitting your skull—typically from above and slightly to one side. Areas facing the light will be brightest, while areas facing away or recessed will be darker.

The eye sockets should be quite dark since they’re deep cavities. Shade them with heavy graphite, leaving perhaps just a small highlight on the rim where light catches the bone.

The nasal cavity is also recessed and should be shaded darkly, especially deep inside. The opening might catch some light around its rim.

The underside of the cheekbones creates a shadow. Shade beneath these bones, blending from dark immediately under the bone to lighter as you move down toward the jaw.

The temporal areas (sides of the skull) are slightly hollow and should receive some middle-tone shading. The very top of the cranium, if your light is coming from above, might be quite light.

Use blending techniques to smooth transitions between light and dark. You can use your finger, a blending stump, or even a piece of tissue. Blend in the direction that follows the skull’s form—circular motions for rounded areas, directional strokes for planes.

Add highlights by lifting graphite with your kneaded eraser. The highest points—perhaps the cheekbones, forehead, or jaw—might have bright highlights where light hits directly.

Step 8: Adding Details and Texture

Small details make your skull drawing more interesting and realistic.

Skulls aren’t perfectly smooth. They have subtle bumps, lines, and texture. You can indicate this with light, varied strokes rather than perfectly blended shading. Small cracks or suture lines (where skull bones join) can add realism.

Teeth have subtle shading too. The surface of each tooth catches light differently. Add a thin shadow line where each tooth meets the gum line. Individual teeth might have slight shading to show their rounded form.

The bone itself has texture. Rather than making it completely smooth, add very light, irregular strokes or stippling to suggest the bone’s surface quality. Don’t overdo this—keep it subtle.

If you want to add more character, you might include slight imperfections, asymmetry, or variations that make your skull unique. Real skulls vary in their proportions and features.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

As you practice drawing skulls, watch out for these common issues:

Making the cranium too small is probably the most frequent mistake. Remember, the brain case is large—about two-thirds of the total skull. Beginners often draw tiny craniums with huge jaws, creating a distorted appearance.

Placing the eye sockets too high or too low throws off the entire face. They should sit roughly halfway up the skull, perhaps slightly below the centerline of the cranium.

Drawing the teeth too large or too detailed can make your skull look cartoonish. Keep teeth relatively small and simple, especially from a distance. Real teeth from a normal viewing distance don’t show every tiny detail.

Using uniform line weight everywhere makes drawings look flat. Vary your lines—darker in deep areas, lighter on edges catching light, and broken lines where form turns away.

Forgetting that skulls are three-dimensional is easy when you’re focusing on features. Always think about how each part exists in space, how it curves, and how light interacts with its form.

Different Angles and Views

Once you’re comfortable with a front view, try other angles to expand your skills.

A three-quarter view shows the skull turned slightly to one side. One eye socket appears larger and more head-on, while the other appears narrower due to perspective. The far side of the skull curves away from view. The centerline becomes a curve following the skull’s roundness.

A profile (side view) shows completely different features. The eye socket becomes an oval opening. The nasal opening is less visible. The teeth show more clearly in a row. The jaw’s shape becomes more prominent, and you can see how it curves up to connect at the temporal area. The skull’s profile has a distinctive shape with the rounded cranium, the face projecting forward, and the jaw angling down and back.

A view from below shows the underside of the skull, including the hard palate (roof of the mouth), the large opening where the spine connects, and the underside of the cheekbones.

An angled top view emphasizes the cranium’s roundness and shows how the face projects downward from it.

Tips for Improving Your Skull Drawings

Practice regularly to build your skills and confidence. Even 15 minutes of sketching helps.

Use reference images constantly. Look at photographs of real skulls from multiple angles. Medical illustrations, museum specimens, or even 3D skull models online provide excellent reference material.

Draw from life if possible. Visiting a natural history museum or owning a replica skull gives you invaluable understanding of three-dimensional form that photographs can’t fully convey.

Start simple and add complexity gradually. Master basic proportions before worrying about every tiny detail. You can always add more detail to future drawings.

Study anatomy resources. Books on artistic anatomy explain not just what the skull looks like but why it has certain features, which deepens your understanding.

Try different styles. While this guide focuses on realistic drawing, explore stylized skulls, cartoon skulls, or decorative skull designs. Each approach teaches you something different.

Applying Your Skull Drawing Skills

Understanding skull structure benefits many types of art:

Portrait drawing becomes much easier when you can visualize the skull beneath the face. You’ll understand why features sit where they do and how they relate to each other.

Character design improves because you can create more believable and diverse faces by varying skull proportions and features.

Fantasy and creature design builds on skull knowledge. Want to create an alien or monster? Start with skull structure and modify it in interesting ways.

Medical and scientific illustration requires accurate skull rendering for educational purposes.

Decorative and graphic art uses skulls in countless ways—from Day of the Dead sugar skulls to tattoo designs to logo elements.

Final Thoughts

Drawing skulls might seem challenging at first, but breaking the process into simple steps makes it approachable for any skill level. Remember that improvement comes with practice. Your first skull drawing might not look perfect, and that’s completely normal. Each attempt teaches you something new about proportion, shading, and form.

Don’t get discouraged if your drawings don’t match your vision immediately. Even experienced artists continue learning and refining their technique. The key is to keep drawing, stay curious, and enjoy the process of improvement.

Start with simple front views using the steps outlined here. As you gain confidence, experiment with different angles, lighting conditions, and styles. Study real skulls whenever possible, and don’t be afraid to make mistakes—they’re essential to learning.

With patience and practice, you’ll soon be creating skull drawings that capture both the technical accuracy and the artistic impact that make this subject so compelling.

10 Frequently Asked Questions About Drawing Skulls

- What’s the most important thing to get right when drawing a skull?

Proportions are the most critical element in skull drawing. The cranium should be approximately two-thirds of the total skull height, with the eye sockets positioned roughly at the midpoint of the overall head. Getting this basic proportion right makes everything else fall into place naturally. Many beginners make the cranium too small and the jaw too large, which throws off the entire drawing. Start with correct proportions, and details become much easier to add convincingly.

- How do I make the eye sockets look hollow and realistic?

Create depth in eye sockets by using graduated shading that gets progressively darker toward the back of the cavity. The darkest areas should be at the top and inner portions of the socket, where the bone curves away from light. Leave a slight highlight on the bottom rim where light might catch the bone edge. Add subtle shading around the socket’s outer edge to show the bone’s thickness. This contrast between the very dark interior and lighter surrounding areas creates that hollow, three-dimensional appearance.

- Do I need to draw every single tooth individually?

For most skull drawings, you don’t need to detail every tooth meticulously. Indicate the general shape and number of teeth, using simple rectangular forms with vertical lines separating them. The front teeth should be slightly more defined since they’re most visible, but teeth further back can be simplified, especially from certain angles. Focus on the overall row and spacing rather than intricate details. Overdrawing teeth can make your skull look cartoonish rather than realistic.

- What’s the best way to practice drawing skulls?

Start by copying from reference photos to understand basic structure and proportions. Then try drawing the same skull from different angles to understand its three-dimensional form. Progress to drawing from life if you can access skull replicas or museum specimens, which teaches you about form in a way photographs cannot. Practice quick gesture sketches to capture overall shape, then do longer studies focusing on details and shading. Regular short practice sessions are more effective than occasional marathon drawing sessions.

- Why does my skull drawing look flat instead of three-dimensional?

Flat-looking skulls usually lack proper shading and value contrast. Skulls have rounded forms, deep cavities, and projecting bones that create shadows and highlights. Add darker values in recessed areas like eye sockets, nasal cavity, and beneath cheekbones. Use mid-tones on curved surfaces, and leave highlights on projecting areas that catch light. Also vary your line weight—using uniform outlines everywhere flattens form. Finally, ensure your initial construction shows the skull as a three-dimensional object rather than just a flat face.

- Should I draw skulls from imagination or always use reference?

Even experienced artists use references for skull drawings because accuracy matters, especially if you want realistic results. The skull has specific proportions and features that are difficult to remember perfectly. However, once you’ve drawn many skulls from reference and understand the structure deeply, you can begin working from memory for loose sketches or stylized work. The best approach is learning from references first, then gradually relying on them less as your understanding grows. Always return to references to refresh your knowledge and catch errors.

- How do I draw skulls from different angles like profile or three-quarter view?

Start by understanding the skull as a three-dimensional form rather than a flat face. When changing angles, your construction process remains similar—begin with basic shapes, then add features—but their appearance changes with perspective. In profile, the eye socket becomes an oval, and you see the jaw’s full curve. In three-quarter view, use perspective to make the near side larger and more detailed while the far side appears smaller and curves away. Practice construction techniques for each angle separately, and study photographic references showing multiple views of the same skull to understand how features transform with rotation.

- What pencil hardness is best for drawing skulls?

A range of pencils serves skull drawing well, but you can start with just an HB or 2B pencil. For more sophisticated shading, use harder pencils (2H or H) for light values and initial construction lines, HB or 2B for mid-tones and general drawing, and softer pencils (4B to 6B) for dark values in deep shadows like eye sockets. Having multiple pencils allows you to achieve a full range of values without pressing too hard or too lightly. However, you can create complete skull drawings with a single pencil by controlling pressure and using blending techniques.

- How can I make my skull drawings look more interesting and artistic rather than just anatomical?

Add artistic flair through dramatic lighting, interesting angles, or stylistic choices. Experiment with strong contrasts between light and shadow, or use unconventional light sources for dramatic effects. Try different artistic styles—detailed realism, loose sketching, stippling, cross-hatching, or even decorative elements like those found in sugar skull designs. Include context like flowers, candles, or symbolic objects. Vary your composition instead of always centering the skull facing forward. Even simple choices like unusual cropping or adding texture to the background make drawings more visually compelling.

- What are common proportional mistakes beginners make with skull drawings?

The most common mistake is making the cranium too small relative to the face, creating a skull that looks bottom-heavy or distorted. Beginners also frequently place eye sockets too high up (should be roughly at the midpoint of the head) or make them too small. Drawing the jaw too wide or too narrow compared to the cranium is another frequent issue—the jaw should be noticeably narrower than the widest point of the cranium. Making teeth too large and prominent also throws off proportions. Finally, not accounting for the skull’s depth and three-dimensionality results in drawings that look flat and unconvincing. Using construction guidelines and measuring relationships between features helps avoid these issues.