What Does Low Creatinine Mean? Understand Low Creatinine Levels with Our Complete Guide

If you’ve recently received blood test results showing low creatinine, you’re probably wondering what it means and whether you should be concerned. Understanding what does low creatinine mean is essential for your health, as creatinine levels serve as an important indicator of kidney function, muscle mass, and overall metabolic health.

Creatinine is a waste product produced by your muscles during normal activity and filtered out of your blood by your kidneys. While most people are familiar with high creatinine levels as a warning sign of kidney problems, low creatinine levels can also indicate underlying health issues that deserve attention. Low creatinine can signal decreased muscle mass, malnutrition, liver disease, pregnancy, or certain chronic conditions, though it’s sometimes completely normal depending on your age, body composition, and lifestyle.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore everything you need to know about low creatinine levels. We’ll explain what creatinine is and why it matters, what’s considered a low level, the numerous causes of low creatinine, symptoms to watch for, potential health implications, diagnostic approaches, treatment options, and strategies for maintaining healthy creatinine levels. Whether you’re concerned about recent lab results, managing a chronic condition, or simply want to understand your body better, this detailed article will provide you with valuable, easy-to-understand information.

What Is Creatinine and Why Does It Matter?

Before understanding what low creatinine means, it’s essential to grasp what creatinine is and why doctors measure it.

Creatinine Basics

Creatinine is a chemical waste product that comes from creatine, a molecule that plays an important role in producing energy for your muscles. Here’s the simple process:

Your muscles contain creatine phosphate (also called phosphocreatine), which provides quick energy for muscle contractions. When your muscles use this energy, they break down creatine phosphate, producing creatinine as a byproduct. This creatinine is released into your bloodstream at a relatively constant rate based on your muscle mass. Your kidneys filter creatinine out of your blood and excrete it through urine. Because healthy kidneys filter creatinine efficiently and muscle mass stays relatively stable, creatinine levels in your blood normally remain fairly consistent.

Why Doctors Measure Creatinine

Healthcare providers use creatinine measurements for several important reasons:

Kidney function assessment: Since kidneys filter creatinine, blood creatinine levels indicate how well your kidneys are working. If kidneys aren’t functioning properly, creatinine builds up in the blood (high creatinine). Conversely, certain conditions can result in lower than normal levels.

Calculating GFR: Creatinine levels are used to calculate your glomerular filtration rate (GFR), which is the best overall measure of kidney function. GFR estimates how much blood your kidneys filter per minute.

Monitoring chronic conditions: For people with kidney disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, or other conditions affecting kidneys or muscles, regular creatinine testing helps track disease progression and treatment effectiveness.

Medication monitoring: Some medications can affect kidney function or muscle mass, so creatinine monitoring helps detect problems early.

Overall health indicator: Creatinine levels can provide insights into muscle mass, nutritional status, hydration, and metabolic function.

How Creatinine Is Measured

Creatinine is typically measured through:

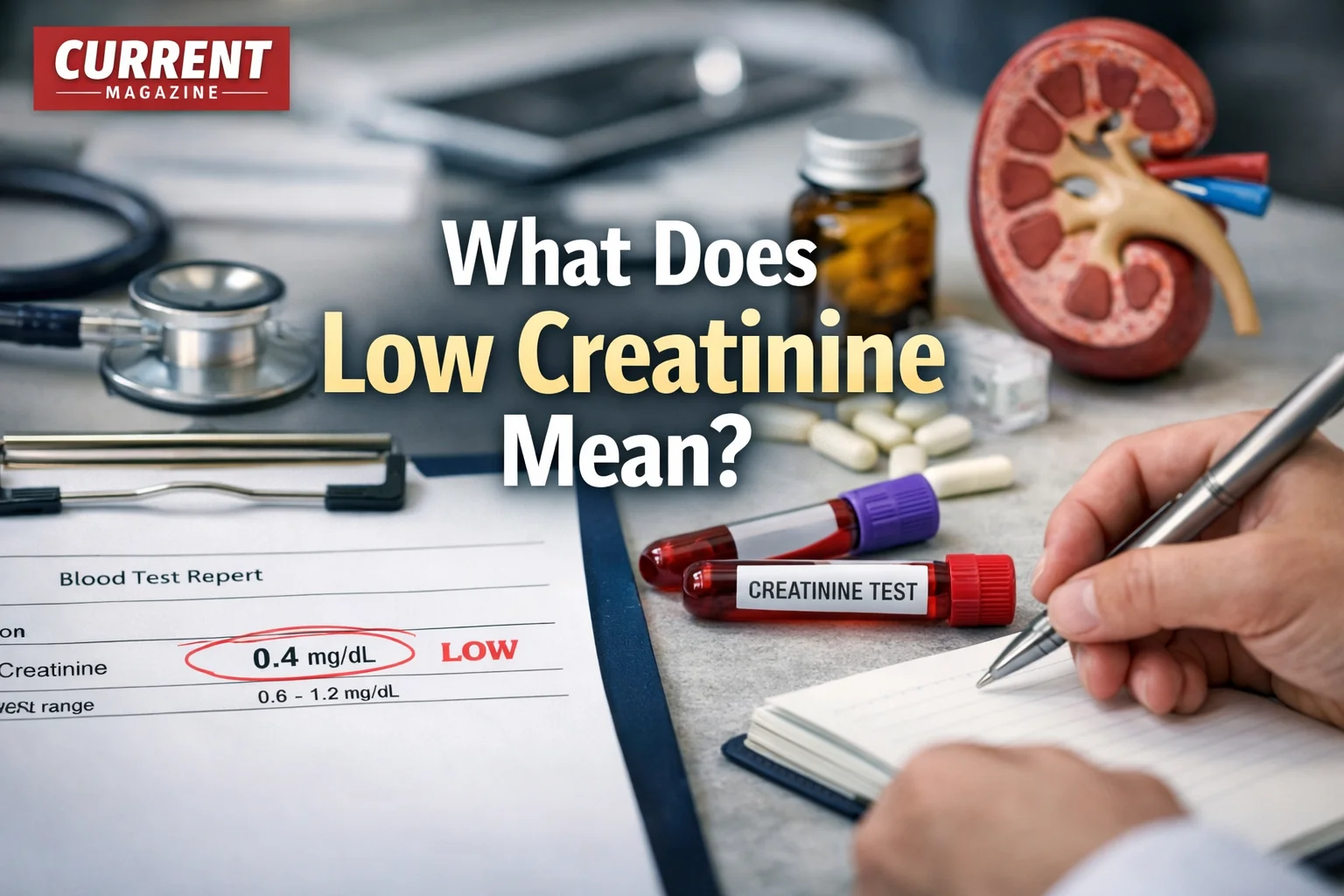

Blood test (serum creatinine): A simple blood draw measures the amount of creatinine in your bloodstream. This is the most common method and is usually included in comprehensive metabolic panels or basic metabolic panels during routine checkups.

Urine test (24-hour urine collection): This measures how much creatinine your body excretes over 24 hours. You collect all urine produced during a 24-hour period in a special container. This test helps calculate creatinine clearance, which directly measures how well kidneys filter creatinine.

Creatinine clearance test: This combines blood and urine tests to calculate exactly how efficiently your kidneys are removing creatinine from your blood.

Normal Creatinine Levels

Understanding what’s “normal” helps you recognize when levels are low:

Adult men: 0.74 to 1.35 mg/dL (milligrams per deciliter) or 65 to 119 µmol/L (micromoles per liter)

Adult women: 0.59 to 1.04 mg/dL or 52 to 92 µmol/L

Children: Levels vary by age and body size, generally ranging from 0.3 to 0.7 mg/dL

Note: Different laboratories may have slightly different reference ranges based on their testing methods, so always compare your results to the specific reference range provided on your lab report.

What Is Considered Low Creatinine?

Low creatinine is generally defined as a level below the normal reference range for your age and sex.

General Guidelines

For adult men: Below 0.74 mg/dL (or below 65 µmol/L)

For adult women: Below 0.59 mg/dL (or below 52 µmol/L)

For children: Below the age-appropriate reference range (varies significantly by age)

Severity Levels

Low creatinine isn’t categorized into severity levels the way high creatinine is, but generally:

Mildly low: Just below the normal range (0.5-0.58 mg/dL for women, 0.6-0.73 mg/dL for men). May not be clinically significant, especially if you’re older, small-framed, or have naturally low muscle mass.

Moderately low: 0.3-0.49 mg/dL. More likely to indicate an underlying condition requiring evaluation.

Very low: Below 0.3 mg/dL. Typically indicates significant muscle wasting, severe malnutrition, or serious liver disease. Requires medical attention.

Important Context

A single low creatinine reading doesn’t automatically mean there’s a serious problem. Your doctor will consider:

- Your individual baseline (some people naturally have lower levels)

- Trends over time (is it decreasing or stable?)

- Your overall health status and symptoms

- Other lab values and clinical findings

- Your age, sex, body size, and muscle mass

- Medications and lifestyle factors

Common Causes of Low Creatinine Levels

Low creatinine can result from numerous conditions and circumstances. Understanding the causes helps you and your doctor identify the underlying issue.

1. Decreased Muscle Mass (Most Common Cause)

Since creatinine is produced by muscles, having less muscle mass means producing less creatinine.

Aging (sarcopenia): As people age, they naturally lose muscle mass—a condition called sarcopenia. This is especially common after age 50 and accelerates after 70. Older adults often have lower creatinine levels simply due to age-related muscle loss, which may be completely normal for their age.

Muscular dystrophy: This group of genetic diseases causes progressive muscle weakness and loss. As muscles deteriorate, creatinine production decreases significantly.

Muscle wasting diseases: Conditions like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), multiple sclerosis, or myasthenia gravis can cause muscle atrophy, reducing creatinine levels.

Immobility or prolonged bed rest: Extended periods without physical activity lead to muscle atrophy. People who are bedridden due to illness, injury, or disability often develop low creatinine levels as their muscles waste away from disuse.

Physical inactivity or sedentary lifestyle: People who rarely exercise or move much may have lower muscle mass than more active individuals, potentially resulting in lower creatinine levels.

Amputation: Loss of limbs means loss of muscle tissue, which can significantly lower creatinine production depending on how much muscle mass was lost.

2. Malnutrition and Dietary Factors

Your diet and nutritional status directly affect muscle mass and creatinine levels.

Protein deficiency: Protein is essential for maintaining muscle mass. Inadequate protein intake over extended periods leads to muscle wasting and decreased creatinine production. This is common in severe malnutrition, eating disorders, extreme poverty, or very restrictive diets.

Overall malnutrition: Insufficient calorie intake causes the body to break down muscle for energy, reducing muscle mass and creatinine levels. This occurs in eating disorders (anorexia nervosa, severe bulimia), poverty and food insecurity, chronic illness affecting appetite, and elderly individuals with poor nutrition.

Vegetarian and vegan diets: While plant-based diets can be perfectly healthy, vegetarians and vegans sometimes have slightly lower creatinine levels than meat-eaters. This is partly because they may have slightly less muscle mass on average and because they don’t consume creatine from meat (though the body produces its own creatine). This is usually not clinically significant.

Very low-calorie diets: Extreme calorie restriction for weight loss can cause muscle loss along with fat loss, potentially lowering creatinine levels.

3. Liver Disease

The liver produces creatine, which muscles then use and convert to creatinine. Severe liver disease can impair this process.

Cirrhosis: Advanced scarring of the liver from chronic liver disease (alcohol-related liver disease, hepatitis B or C, fatty liver disease, autoimmune hepatitis) can reduce creatine production, leading to low creatinine levels.

Acute liver failure: Sudden, severe liver damage dramatically reduces liver function, including creatine synthesis.

Severe hepatitis: Serious liver inflammation can temporarily impair creatine production.

Why liver disease causes low creatinine: When the liver can’t produce adequate creatine, muscles have less substrate to convert into creatinine. Additionally, liver disease often causes muscle wasting (sarcopenia) and malnutrition, compounding the effect.

4. Pregnancy

Pregnant women commonly have lower creatinine levels, especially in the second and third trimesters.

Why pregnancy lowers creatinine: Increased blood volume during pregnancy dilutes blood concentration of creatinine (dilutional effect). Increased glomerular filtration rate (GFR) during pregnancy means kidneys filter more blood and excrete more creatinine. Hormonal changes affect creatinine production and excretion. Growing fetus and placenta affect maternal metabolism.

This is normal: Low creatinine during pregnancy is typically not a concern and is considered a normal physiological change. However, very low levels or other abnormal kidney function tests should still be evaluated.

5. Chronic Illness and Inflammation

Various chronic diseases can contribute to low creatinine through multiple mechanisms.

Cancer: Many cancers cause cachexia (severe weight loss and muscle wasting), significantly reducing muscle mass and creatinine production. Chemotherapy can also affect muscle mass and kidney function.

Chronic kidney disease (paradoxical): While advanced kidney disease typically causes high creatinine, some people with kidney disease have low muscle mass from chronic illness, malnutrition, or dialysis-related protein loss, resulting in deceptively low or “normal” creatinine despite poor kidney function.

Heart failure: Severe, chronic heart failure can cause cardiac cachexia (muscle wasting), reducing creatinine levels.

Chronic infections: Long-term infections like HIV/AIDS or tuberculosis can cause wasting syndrome and muscle loss.

Inflammatory conditions: Chronic inflammation from conditions like rheumatoid arthritis or inflammatory bowel disease can contribute to muscle loss over time.

6. Medications

Certain medications can affect creatinine levels.

Corticosteroids: Long-term steroid use (prednisone, dexamethasone) can cause muscle wasting and protein breakdown, potentially lowering creatinine levels, especially with chronic high-dose use.

Immunosuppressants: Some medications that suppress the immune system may affect muscle mass or creatinine metabolism.

Certain antibiotics: Some antibiotics may interfere with creatinine measurement (laboratory interference) rather than actually changing true creatinine levels.

Diuretics: In some cases, excessive use of water pills can affect creatinine levels through changes in hydration and kidney function.

7. Excessive Hydration (Dilutional Effect)

Drinking enormous amounts of water can temporarily dilute blood creatinine concentration, making levels appear low.

When this happens: People drinking excessive water for medical tests or procedures, athletes overhydrating before competitions, people with psychogenic polydipsia (compulsive water drinking, often associated with psychiatric conditions), or deliberate overhydration to affect drug tests.

Temporary effect: This is usually temporary and corrects when fluid intake normalizes. True dilutional low creatinine from overhydration is relatively uncommon in everyday situations.

8. Hyperthyroidism

Overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism) increases metabolism, which can affect muscle mass and creatinine levels.

Mechanism: Excess thyroid hormone increases protein breakdown, potentially causing muscle loss. Increased metabolic rate affects creatinine production and clearance. Hyperthyroidism can cause weight loss including muscle mass.

Usually accompanies other symptoms: Low creatinine from hyperthyroidism typically occurs alongside classic thyroid symptoms (rapid heartbeat, weight loss, tremor, anxiety, heat intolerance).

9. Small Body Frame or Low Muscle Mass (Constitutional)

Some people naturally have small frames, low muscle mass, or smaller body size, resulting in lower creatinine production.

When this is normal: Petite women or men, people who are naturally thin with little muscle development, individuals with genetic predisposition to smaller stature and less muscle mass, or children and adolescents (age-appropriate lower levels).

Not pathological: If you’ve always had low creatinine levels, have proportionate low muscle mass for your body type, and are otherwise healthy, this may simply be your normal baseline.

10. Rare Genetic Conditions

Certain genetic disorders can affect creatine and creatinine metabolism.

Creatine deficiency syndromes: Rare genetic disorders affecting creatine synthesis or transport can result in very low creatinine levels. These typically present in childhood with developmental delays, intellectual disability, and seizures.

Genetic muscle disorders: Various inherited conditions affecting muscle development or function can lead to low muscle mass and consequently low creatinine.

Symptoms Associated With Low Creatinine

Low creatinine itself doesn’t cause symptoms—it’s a laboratory finding. However, the underlying conditions causing low creatinine often produce noticeable symptoms.

Symptoms of Low Muscle Mass

If your low creatinine results from decreased muscle mass, you might experience:

- Visible muscle wasting or thinning of arms and legs

- Weakness and fatigue, difficulty performing daily activities

- Reduced exercise tolerance or endurance

- Difficulty climbing stairs or rising from a chair

- Loss of grip strength

- Weight loss, particularly loss of lean body mass

- Increased risk of falls and fractures (due to weakness)

- Slowed recovery from illness or injury

Symptoms of Malnutrition

If nutritional deficiency is the cause:

- Unintentional weight loss

- Feeling weak and tired constantly

- Difficulty concentrating or “brain fog”

- Brittle hair and nails

- Dry, thin, or pale skin

- Feeling cold frequently

- Slow wound healing

- Frequent infections (weakened immune system)

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

- In severe cases: swelling (edema) despite low weight

Symptoms of Liver Disease

If liver problems are causing low creatinine:

- Yellowing of skin and eyes (jaundice)

- Abdominal swelling and pain (ascites)

- Swelling in legs and ankles

- Fatigue and weakness

- Dark urine and pale stools

- Nausea and loss of appetite

- Easy bruising and bleeding

- Itchy skin

- Confusion or difficulty thinking (hepatic encephalopathy in advanced disease)

- Spider-like blood vessels on skin

Symptoms of Chronic Illness

Depending on the specific condition:

- Disease-specific symptoms (e.g., joint pain in rheumatoid arthritis, shortness of breath in heart failure)

- Chronic fatigue and weakness

- Unintended weight loss

- Reduced quality of life

- Difficulty maintaining normal activities

When Low Creatinine Has No Symptoms

In many cases, low creatinine is discovered incidentally during routine blood work and you may feel completely fine. This is common when:

- You naturally have low muscle mass due to body type

- You’re older and experiencing age-appropriate muscle loss

- You’re pregnant (normal physiological change)

- You follow a vegetarian diet and have slightly lower levels

- You have mild reduction that isn’t clinically significant

The absence of symptoms doesn’t mean low creatinine should be ignored—discuss results with your doctor to determine if further investigation is needed.

Health Implications and Risks of Low Creatinine

Understanding the potential health implications of low creatinine helps you appreciate why it warrants medical attention.

Indicator of Underlying Disease

Low creatinine’s primary significance is that it can signal serious underlying health conditions:

Liver disease: As discussed, severe liver dysfunction can cause low creatinine and carries serious health risks including liver failure, bleeding disorders, increased infection risk, and increased risk of liver cancer (in cirrhosis).

Muscle-wasting diseases: Conditions causing muscle loss can lead to disability, increased fall risk, reduced quality of life, and difficulty with daily activities and self-care.

Malnutrition: Severe nutritional deficiency causes immune system weakness (increased infections), organ dysfunction, impaired wound healing, increased mortality risk, and in extreme cases, death from starvation.

Chronic diseases: Low creatinine from cancer, heart failure, or other chronic conditions indicates advanced disease and typically poorer prognosis.

Muscle Mass and Functional Decline

Low muscle mass indicated by low creatinine has direct health consequences:

Frailty: Reduced muscle mass contributes to frailty, especially in older adults, making you more vulnerable to illness, injury, and hospitalization.

Falls and fractures: Weak muscles increase fall risk, and falls can cause fractures, hospitalization, loss of independence, and increased mortality in elderly individuals.

Reduced mobility: Loss of muscle strength and mass limits mobility, affecting quality of life and ability to perform daily activities independently.

Metabolic effects: Muscle tissue plays important roles in metabolism, including glucose regulation. Low muscle mass is associated with increased risk of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes.

Difficulty Assessing Kidney Function

Low creatinine can actually mask kidney problems, creating a diagnostic challenge:

Deceptively “normal” creatinine: Someone with both low muscle mass and kidney disease might have creatinine levels in the “normal” range despite poor kidney function. The low muscle mass produces less creatinine, while impaired kidneys retain what little is produced, balancing out to appear normal.

Why this matters: Kidney disease might go undetected in people with low muscle mass if doctors rely solely on creatinine levels. This is why doctors use equations that account for age, sex, and race when calculating GFR—to help correct for muscle mass differences.

Cystatin C testing: For people with very low muscle mass, doctors may order cystatin C (another marker of kidney function not dependent on muscle mass) to get a more accurate picture of kidney health.

Nutritional Concerns

Persistently low creatinine from inadequate nutrition suggests:

Protein-energy malnutrition: Insufficient protein and calories compromise health in multiple ways.

Micronutrient deficiencies: People with protein deficiency often also lack essential vitamins and minerals (iron, B vitamins, vitamin D, calcium, etc.).

Immune suppression: Malnutrition weakens immune function, increasing infection risk.

Delayed development: In children, malnutrition and low creatinine can indicate failure to thrive, potentially causing long-term developmental problems.

Increased Mortality Risk

Research has shown associations between low creatinine and increased mortality risk in certain populations:

Elderly populations: Studies show that older adults with very low creatinine levels have higher mortality rates than those with normal levels, likely because low creatinine indicates frailty, malnutrition, and multiple chronic conditions.

Hospitalized patients: Low creatinine in hospital settings is associated with worse outcomes, longer hospital stays, and increased death risk.

Chronic disease patients: In people with heart failure, liver disease, or cancer, very low creatinine indicates advanced disease and poorer prognosis.

Important Note on Risk

Low creatinine itself doesn’t cause these risks—rather, it’s a marker of conditions that carry these risks. Treating the underlying cause is what improves outcomes, not simply raising creatinine levels.

Diagnosing the Cause of Low Creatinine

When low creatinine is discovered, your doctor will work to identify the underlying cause through systematic evaluation.

Initial Assessment

Medical history review: Your doctor will ask detailed questions about your symptoms, medical conditions, medications and supplements, diet and nutrition, exercise habits, alcohol use, family history, recent weight changes, and any known liver or kidney problems.

Physical examination: A thorough exam will assess muscle mass and body composition, signs of malnutrition (skin, hair, nail changes), signs of liver disease (jaundice, ascites, spider angiomas), neurological function, and overall health status.

Laboratory Tests

Additional blood and urine tests help pinpoint the cause:

Comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP): Includes liver function tests (ALT, AST, bilirubin, albumin) to check for liver disease, electrolytes and kidney function markers, glucose and calcium levels.

Complete blood count (CBC): Can reveal anemia (common with malnutrition or chronic disease), infection or inflammation, and other blood abnormalities.

Albumin and total protein: Low levels suggest malnutrition, liver disease, or protein loss through kidneys.

Thyroid function tests (TSH, free T4): Check for hyperthyroidism if suspected.

Cystatin C: Alternative kidney function marker not dependent on muscle mass, providing more accurate kidney function assessment in people with low muscle mass.

Creatine kinase (CK): Enzyme released when muscle is damaged; helps diagnose muscle disorders.

24-hour urine collection: Measures total creatinine excretion and can calculate creatinine clearance for more accurate kidney function assessment.

Specific protein markers: Depending on suspected cause, tests for inflammatory markers (CRP, ESR), cancer markers, or specific antibodies.

Specialized Testing

Based on initial findings, your doctor might order:

Imaging studies:

- Ultrasound, CT scan, or MRI of abdomen to evaluate liver, kidneys, and other organs

- DEXA scan (dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry) to measure body composition and muscle mass

- MRI of muscles if muscle disease is suspected

Body composition analysis: More detailed assessment of muscle mass, fat mass, and overall body composition using DEXA, bioelectrical impedance, or other methods.

Liver biopsy: If liver disease is suspected but not confirmed by other tests, a tissue sample may be examined.

Muscle biopsy: Rarely needed, but if a specific muscle disorder is suspected, examining muscle tissue can provide diagnosis.

Nutritional assessment: Evaluation by a dietitian to assess dietary intake, nutritional status, and deficiencies.

Genetic testing: If a hereditary condition is suspected (muscle disorders, creatine deficiency syndromes).

Functional assessments: Tests of muscle strength, grip strength, walking speed, and ability to perform daily activities can objectively measure functional impact of low muscle mass.

Differential Diagnosis

Your doctor will consider and rule out various possibilities:

- Is this normal variation for your body type and age?

- Is there evidence of muscle wasting? If so, what’s causing it?

- Are there signs of malnutrition or inadequate protein intake?

- Is liver disease present?

- Could medications be contributing?

- Are there chronic illnesses affecting muscle mass?

- Is this pregnancy-related?

- Are kidney function estimates accurate given the low creatinine?

Pattern Recognition

Doctors look at the complete picture:

- A frail, elderly person with low creatinine likely has age-related muscle loss

- Low creatinine with abnormal liver enzymes suggests liver disease

- Low creatinine in someone with eating disorder points to malnutrition

- Low creatinine with muscle weakness and elevated CK suggests muscle disease

- Low creatinine during pregnancy is likely physiological

Treatment and Management of Low Creatinine

Treatment focuses on addressing the underlying cause rather than the creatinine level itself. Creatinine is a marker, not a disease.

1. Addressing Muscle Loss

If low creatinine results from decreased muscle mass:

Resistance training and exercise: Progressive strength training (weight lifting, resistance bands, bodyweight exercises) is the most effective way to build muscle mass. Aim for 2-3 sessions per week targeting all major muscle groups. Include compound exercises like squats, deadlifts, push-ups, and rows. Start gradually, especially if you’re older or have been inactive, and work with a physical therapist or qualified trainer if needed. Even older adults can build muscle with appropriate exercise programs.

Adequate protein intake: Consume 1.2-2.0 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight daily (higher end for older adults or those building muscle). Include protein at each meal for optimal muscle protein synthesis. Good sources include lean meats, poultry, fish, eggs, dairy products, legumes, nuts, and protein supplements if needed. Older adults may need higher protein intake than younger people to maintain muscle mass.

Overall good nutrition: Ensure adequate calorie intake to support muscle building (your body needs energy to build tissue). Include all macronutrients—protein, healthy fats, and carbohydrates. Get sufficient vitamins and minerals, particularly vitamin D (important for muscle function), B vitamins, and minerals like magnesium and potassium.

Physical therapy: For people with muscle weakness from disease or injury, physical therapy can help rebuild strength safely and effectively, improve functional ability, and prevent further decline.

2. Treating Malnutrition

If nutritional deficiency is the cause:

Dietary intervention: Increase calorie intake with nutrient-dense foods. Boost protein consumption significantly. Eat frequent, smaller meals if large meals are difficult. Include high-calorie, nutritious snacks. Use protein supplements or meal replacement shakes if needed.

Nutritional counseling: Work with a registered dietitian who can assess your specific nutritional needs, create personalized meal plans, address barriers to adequate nutrition, and monitor progress.

Address underlying eating disorders: If anorexia, bulimia, or other eating disorders are causing malnutrition, comprehensive treatment is essential including psychological therapy, nutritional rehabilitation, medical monitoring, and possibly inpatient treatment for severe cases.

Treat conditions affecting appetite: Address depression, nausea, pain, or other symptoms that reduce appetite. Modify medications that suppress appetite if possible. Manage digestive symptoms that interfere with eating.

Nutritional supplements: Oral nutritional supplements (like Ensure, Boost) can help increase calorie and protein intake. Vitamin and mineral supplementation to correct deficiencies. In severe cases, enteral nutrition (feeding tube) or parenteral nutrition (IV nutrition) may be necessary temporarily.

3. Managing Liver Disease

If liver disease is the underlying cause:

Treat the specific liver condition: Antiviral medications for hepatitis B or C. Alcohol cessation for alcohol-related liver disease. Weight loss and metabolic management for fatty liver disease. Immunosuppressants for autoimmune hepatitis. Treatment of underlying causes prevents further liver damage.

Supportive care for cirrhosis: Medications to manage complications (fluid retention, bleeding risk, infections). Dietary modifications (adequate protein but not excessive, sodium restriction). Regular monitoring for liver cancer. In advanced cases, evaluation for liver transplantation.

Avoid further liver damage: Complete alcohol abstinence. Avoid hepatotoxic medications and supplements. Maintain healthy weight. Get vaccinated against hepatitis A and B if not immune.

Nutritional support: People with liver disease often need specialized nutritional management to prevent or treat malnutrition while avoiding excessive protein that might worsen hepatic encephalopathy (though this is less of a concern with modern understanding—adequate protein is usually important).

4. Managing Chronic Diseases

For low creatinine from chronic illnesses:

Optimize disease management: Work with specialists to control the underlying condition. Take medications as prescribed. Monitor disease progression and adjust treatment as needed.

Prevent and treat cachexia: Cancer or heart failure-related cachexia requires specialized nutritional interventions, medications that may stimulate appetite or reduce muscle wasting, physical activity as tolerated, and treating symptoms (pain, nausea, depression) that worsen wasting.

Comprehensive supportive care: Address all aspects of chronic disease including symptom management, psychological support, palliative care when appropriate, and quality of life considerations.

5. Medication Management

If medications contribute to low creatinine:

Review with your doctor: Never stop medications without consulting your physician. Discuss whether medications could be contributing to muscle loss or low creatinine. Consider alternatives if appropriate. Weigh benefits vs. risks of continuing medications.

Steroid management: If long-term corticosteroids are necessary, use the lowest effective dose, incorporate muscle-preserving strategies (exercise, adequate protein), and monitor muscle mass and function regularly.

6. Treating Hyperthyroidism

If overactive thyroid is the cause:

Antithyroid medications: Drugs like methimazole reduce thyroid hormone production.

Radioactive iodine: Destroys overactive thyroid tissue.

Surgery: Removal of part or all of the thyroid gland in some cases.

Beta-blockers: Control symptoms while treating the underlying condition.

Once hyperthyroidism is controlled, creatinine levels typically normalize as metabolism stabilizes and muscle mass improves.

7. Addressing Pregnancy-Related Low Creatinine

For pregnant women with low creatinine:

Usually requires no treatment: Low creatinine during pregnancy is typically normal and physiological.

Monitor kidney function: Ensure kidney function is otherwise normal through regular prenatal care.

Address any complications: If very low creatinine is accompanied by other abnormalities, investigate further.

Postpartum normalization: Creatinine levels typically return to pre-pregnancy baseline within weeks after delivery.

8. General Supportive Measures

Regardless of the specific cause:

Regular monitoring: Periodic blood tests to track creatinine levels and assess whether interventions are working.

Adequate hydration: Maintain proper fluid intake (but avoid overhydration).

Address modifiable risk factors: Quit smoking, limit alcohol, maintain healthy weight, get adequate sleep, and manage stress.

Preventive care: Stay current with health screenings, vaccinations, and preventive measures.

Multidisciplinary approach: Depending on your situation, you may benefit from care coordinated among primary care doctor, specialists (hepatologist, nephrologist, endocrinologist, etc.), dietitian, physical therapist, and other healthcare providers.

Prevention: Maintaining Healthy Creatinine Levels

While you can’t always prevent conditions that cause low creatinine, you can take steps to maintain muscle mass and overall health.

Build and Maintain Muscle Mass

Regular strength training: Engage in resistance exercise 2-3 times weekly throughout your life, not just when muscle loss becomes a problem. Muscle building becomes more difficult with age, so maintenance is key.

Stay physically active: In addition to strength training, include regular cardiovascular exercise, flexibility work, and daily movement to maintain overall fitness and muscle function.

Start early: Building good muscle mass when you’re young provides a reserve for later life when muscle naturally declines.

Maintain Activity as You Age

Continue exercising: Don’t become sedentary as you get older. Adapt exercises to your abilities rather than stopping altogether.

Use it or lose it: Regular use of muscles through daily activities, hobbies, and exercise prevents disuse atrophy.

Fall prevention: Prevent injuries that could lead to immobility and subsequent muscle loss through home safety modifications, appropriate footwear, vision correction, and balance exercises.

Nutrition Throughout Life

Adequate protein: Consistently consume enough protein for your needs (increases with age—older adults need more protein than younger adults to maintain muscle).

Balanced diet: Eat a variety of nutrient-dense foods providing all essential nutrients.

Sufficient calories: Avoid prolonged very low-calorie diets that cause muscle loss along with fat loss.

Prevent malnutrition: Address appetite, dental, financial, or other barriers to adequate nutrition promptly.

Protect Your Liver

Limit alcohol: Excessive alcohol consumption is a leading cause of liver disease. If you drink, do so in moderation or abstain entirely.

Prevent viral hepatitis: Get vaccinated against hepatitis A and B. Practice safe behaviors to prevent hepatitis C.

Maintain healthy weight: Obesity increases risk of fatty liver disease, which can progress to cirrhosis.

Medication caution: Avoid excessive acetaminophen (Tylenol), avoid sharing needles, and be cautious with herbal supplements that may harm the liver.

Manage Chronic Conditions

Control underlying diseases: Well-managed diabetes, heart disease, autoimmune conditions, and other chronic illnesses are less likely to cause muscle wasting.

Take medications as prescribed: Proper disease control prevents complications.

Regular medical care: Don’t skip appointments or monitoring tests.

Monitor Your Health

Regular checkups: Routine physical exams and blood work can detect problems early.

Pay attention to changes: Notice and report unintentional weight loss, increasing weakness, or other concerning symptoms.

Track muscle mass: If you’re at risk for muscle loss, periodic body composition assessments can detect changes before they become severe.

Healthy Lifestyle Habits

Don’t smoke: Smoking contributes to numerous conditions that can affect muscle mass and overall health.

Manage stress: Chronic stress affects overall health and can contribute to poor nutrition and inactivity.

Get adequate sleep: Sleep is essential for muscle recovery and overall health.

Stay socially connected: Social isolation is associated with poor nutrition and reduced physical activity in older adults.

Special Populations and Low Creatinine

Certain groups have unique considerations regarding low creatinine.

Older Adults (Elderly)

Common in aging: Low creatinine becomes increasingly common with age due to age-related muscle loss (sarcopenia), reduced physical activity, changes in metabolism, and chronic illness.

Clinical significance: Very low creatinine in elderly individuals is associated with frailty, increased fall risk, higher mortality, and reduced quality of life.

Interventions: Even very elderly individuals can benefit from strength training and increased protein intake to preserve muscle mass and function. Resistance exercise programs have been shown effective even in people in their 80s and 90s.

Careful assessment needed: Low creatinine might mask kidney disease in elderly patients with low muscle mass, requiring additional testing beyond creatinine alone.

Children and Adolescents

Age-appropriate ranges: Children have lower creatinine than adults, and levels increase as they grow and develop more muscle mass.

Concerning signs: Low creatinine for age might indicate malnutrition, failure to thrive, muscle disorders, or rare metabolic conditions.

Growth monitoring: Tracking growth curves, development, and muscle development alongside creatinine helps identify problems.

Pregnant Women

Expected decrease: Creatinine levels normally drop during pregnancy, especially in second and third trimesters.

Usually not concerning: This physiological change doesn’t require treatment and resolves after delivery.

Monitor kidney function: Ensure other kidney function markers are normal and watch for signs of pregnancy complications like preeclampsia.

Athletes and Highly Muscular Individuals

Higher baseline: Very muscular people typically have higher creatinine levels than average due to greater muscle mass.

If levels are low: This is unusual in athletes and might indicate overtraining with inadequate nutrition, illness or infection, inadequate protein intake, or dehydration (though dehydration usually increases creatinine).

Vegetarians and Vegans

Slightly lower levels: People following plant-based diets often have somewhat lower creatinine levels than meat-eaters.

Usually not problematic: Mild reduction is common and not necessarily concerning if you’re otherwise healthy.

Ensure adequate protein: Plant-based protein sources (legumes, tofu, tempeh, seitan, nuts, seeds, whole grains) should be consumed in adequate amounts.

Consider supplementation: Some vegetarians/vegans benefit from creatine supplementation, especially if involved in high-intensity exercise.

People With Disabilities or Limited Mobility

High risk for low creatinine: Individuals with paralysis, severe arthritis, or other conditions limiting movement are at high risk for muscle wasting.

Preservation strategies: Physical therapy within physical limitations, passive range of motion exercises, adequate nutrition, preventing pressure sores and complications of immobility.

Chronic Disease Patients

Multiple factors: People with chronic diseases face multiple risks for low creatinine including the disease process itself, medications, reduced activity, poor appetite, and chronic inflammation.

Comprehensive management: Requires addressing the primary disease, nutritional support, appropriate physical activity, and careful medication management.

When to See Your Doctor

While one isolated low creatinine result may not be concerning, certain situations warrant medical attention.

You Should Consult Your Doctor If:

You have symptoms of the underlying conditions discussed earlier (unexplained weight loss, muscle weakness, jaundice, severe fatigue, etc.).

Your creatinine is very low (below 0.3 mg/dL), which suggests a significant underlying problem.

Creatinine is declining over time on serial tests, indicating progressive muscle loss or worsening condition.

You have risk factors for liver disease, muscle disorders, or malnutrition.

You’re experiencing unintentional weight loss, especially rapid or substantial loss.

You have known liver disease or other chronic conditions that could affect creatinine.

You’re elderly with very low creatinine and signs of frailty.

Your low creatinine is accompanied by other abnormal lab results, suggesting a complex problem.

You have concerns about your results, even if your doctor initially says they’re not worried—it’s reasonable to request explanation and follow-up.

Questions to Ask Your Doctor

When discussing low creatinine, consider asking:

- What is my exact creatinine level and how does it compare to normal ranges?

- Is this a new finding or have my levels been decreasing over time?

- What do you think is causing my low creatinine?

- Do I need additional tests to determine the cause?

- Should I be concerned about my kidney function being masked by low muscle mass?

- Are there treatments or lifestyle changes that would help?

- How often should my creatinine be monitored going forward?

- Could any of my medications be contributing to this?

- Should I see a specialist (nephrologist, hepatologist, endocrinologist, etc.)?

- What symptoms should prompt me to come back sooner?

The Bottom Line: Understanding Your Low Creatinine

Low creatinine levels serve as an important health marker that can reveal underlying conditions requiring attention. While a slightly low reading may be completely normal for your body type and circumstances, more significant reductions often point to meaningful health issues affecting muscle mass, nutrition, liver function, or overall metabolic health.

Key Takeaways:

Low creatinine has many potential causes ranging from benign (small body frame, aging, pregnancy) to serious (liver disease, severe malnutrition, muscle-wasting diseases).

Context matters immensely: A single low reading should be interpreted in the context of your age, body composition, symptoms, medical history, and other lab results.

The underlying cause, not the number itself, is what matters. Treatment focuses on addressing the root problem (building muscle, improving nutrition, treating liver disease) rather than simply raising creatinine levels.

Low creatinine can mask kidney problems in people with low muscle mass, making accurate kidney function assessment more challenging.

Prevention is possible: Maintaining muscle mass through resistance exercise and adequate protein intake throughout life helps prevent low creatinine from muscle loss.

Medical evaluation is important: If you have low creatinine, especially if it’s very low, declining over time, or accompanied by symptoms, consult your doctor for proper evaluation.

Many causes are treatable: Whether it’s malnutrition, muscle disuse, or manageable chronic conditions, interventions exist to address most causes of low creatinine.

Don’t ignore the finding: While low creatinine sometimes represents normal variation, it can also be an early warning sign of conditions that are easier to treat when caught early.

If your lab results show low creatinine, don’t panic, but don’t dismiss it either. Use it as an opportunity to have a conversation with your healthcare provider about your overall health, muscle mass, nutritional status, and any underlying conditions that might need attention. With proper evaluation and appropriate interventions, most causes of low creatinine can be effectively managed, helping you maintain your health, strength, and quality of life for years to come.

10 Frequently Asked Questions About Low Creatinine

1. Can low creatinine levels be dangerous, or is it always less serious than high creatinine?

While high creatinine typically indicates kidney disease and gets more attention, low creatinine can also signal serious health problems and shouldn’t be dismissed. The danger depends entirely on the underlying cause. Very low creatinine from severe malnutrition, advanced liver disease, or significant muscle-wasting conditions can be quite serious and is associated with increased mortality risk in some populations. For example, low creatinine in elderly individuals often indicates frailty and is associated with higher death rates, increased fall risk, and reduced quality of life. Low creatinine from advanced cirrhosis signals severe liver dysfunction with potentially life-threatening complications. However, mildly low creatinine from normal variation, small body size, vegetarian diet, or pregnancy is generally not dangerous at all. The key is determining the cause—some are completely benign while others require urgent medical attention. Additionally, low creatinine can be problematic because it may mask kidney disease in people with low muscle mass, potentially delaying diagnosis and treatment of kidney problems. Always discuss low creatinine results with your doctor to determine if further evaluation is needed based on your individual circumstances.

2. I’m a vegetarian/vegan with low creatinine—should I start eating meat or take creatine supplements?

Vegetarians and vegans commonly have slightly lower creatinine levels than meat-eaters, and this is usually not a health concern if you’re otherwise healthy and consuming adequate protein from plant sources. You don’t need to start eating meat simply because of mildly low creatinine. The slight reduction occurs because plant-based diets don’t provide dietary creatine (found in meat and fish), though your body makes its own creatine from amino acids, and because vegetarians may have slightly less muscle mass on average. If your creatinine is only mildly low, you’re maintaining stable weight and muscle mass, you’re eating adequate plant-based protein (legumes, tofu, tempeh, seitan, nuts, seeds, whole grains), and you feel healthy and strong, no intervention is needed. However, if your creatinine is very low or if you’re experiencing muscle loss, weakness, or other symptoms, focus first on ensuring adequate protein and calorie intake. A registered dietitian can help optimize your plant-based diet. Creatine supplementation is an option if you’re an athlete or do high-intensity exercise—creatine supplements are typically vegan (made synthetically) and can improve performance and muscle mass. However, supplementation for the sole purpose of raising creatinine levels (without athletic goals) isn’t necessary. The bottom line: Mildly low creatinine on a healthy, well-planned plant-based diet is normal and not concerning.

3. Can I raise my creatinine levels by eating more protein or taking creatine supplements?

Yes, increasing protein intake and muscle mass will naturally raise creatinine levels over time, and creatine supplementation can also increase creatinine. However, the goal shouldn’t be to raise creatinine for its own sake—the goal should be addressing the underlying cause. If your low creatinine results from inadequate protein intake and muscle loss, then yes, increasing dietary protein (aim for 1.2-2.0 grams per kilogram of body weight daily) combined with resistance training will help rebuild muscle mass, which will gradually raise creatinine levels as a beneficial side effect. Good protein sources include meat, poultry, fish, eggs, dairy, legumes, nuts, and soy products. Creatine supplements (typically 3-5 grams daily) increase the body’s creatine stores, which can enhance exercise performance, promote muscle growth, and consequently raise creatinine levels. However, supplementation is most appropriate for athletes or people doing high-intensity training, not as a treatment specifically for low creatinine. Important caution: Simply raising creatinine without addressing underlying problems (like liver disease or malnutrition) doesn’t improve health—it just makes the lab number look better while the actual problem continues. Work with your doctor to identify and treat the cause of low creatinine rather than just trying to raise the number.

4. I’m elderly with low creatinine—is this just normal aging or something I should worry about?

Age-related muscle loss (sarcopenia) is extremely common and results in lower creatinine levels in older adults, so some reduction is expected with aging. However, “common” doesn’t mean “optimal” or that it should be ignored. While mild reduction may be normal for your age, very low creatinine in elderly individuals is associated with frailty, increased fall and fracture risk, reduced functional independence, higher hospitalization rates, and increased mortality. Therefore, it deserves attention and intervention even if it’s “expected.” The good news is that resistance training and adequate protein intake can help preserve and even build muscle mass even in people in their 70s, 80s, and beyond—it’s never too late to benefit from strength training. Older adults should aim for 1.2-1.5 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight daily (higher than younger adults) and engage in resistance exercise 2-3 times weekly if physically able. Work with your doctor to assess whether your low creatinine represents normal aging or if it indicates malnutrition, underlying illness, or excessive frailty that needs more aggressive intervention. Physical therapy can help design safe, effective exercise programs for older adults. Additionally, very low creatinine might mask kidney disease in elderly patients with low muscle mass, so your doctor may want to check other kidney function markers like cystatin C to ensure accurate assessment.

5. How quickly can I expect my creatinine levels to increase with treatment?

The timeline for creatinine levels to rise depends entirely on the underlying cause and the interventions used. If you’re building muscle mass through resistance training and increased protein intake, expect gradual change over weeks to months—you won’t see overnight results. Muscle building is a slow process, especially as we age. You might see measurable improvements in muscle mass and creatinine levels after 8-12 weeks of consistent strength training and adequate nutrition, though it may take longer for significant changes. If malnutrition is being treated, creatinine may start rising within several weeks as nutritional status improves and muscle mass begins recovering, but severe, long-standing malnutrition may take months to fully correct. For liver disease, if the underlying liver condition can be treated (like successful treatment of hepatitis C or abstinence from alcohol in alcohol-related liver disease), liver function may improve over months, potentially increasing creatinine production. However, advanced cirrhosis may not be reversible. For pregnancy-related low creatinine, levels typically return to pre-pregnancy baseline within a few weeks after delivery. For medication-related causes, creatinine might improve gradually after stopping or changing the offending medication, though this depends on how much muscle loss has occurred. Regular monitoring every 2-3 months can track progress. Remember, the goal isn’t just raising creatinine—it’s improving the underlying health issue, whether that’s muscle mass, nutritional status, or liver function.

6. Does low creatinine mean my kidneys are working too well or filtering too much?

This is a common misconception. Low creatinine doesn’t mean your kidneys are “overworking” or filtering too efficiently. Creatinine levels primarily reflect how much creatinine your muscles produce, not how well your kidneys filter (although kidney function does affect it). If your muscles produce very little creatinine (due to low muscle mass), there’s simply less creatinine in your blood regardless of how well your kidneys function. However, pregnancy is one situation where increased kidney filtration does contribute to low creatinine—pregnant women have increased glomerular filtration rate (GFR), meaning their kidneys filter more blood per minute, which helps clear creatinine from the blood more quickly, contributing to the lower levels along with dilutional effects. In most other situations, low creatinine is about low production, not excessive filtration. In fact, low creatinine can sometimes mask kidney disease because if your muscles aren’t producing much creatinine, even poorly functioning kidneys can clear the small amount being produced, resulting in a “normal” or low creatinine level despite impaired kidney function. This is why doctors use formulas that account for age, sex, and sometimes race when calculating estimated GFR (eGFR) from creatinine—to help correct for muscle mass differences and get a more accurate picture of kidney function.

7. I have low creatinine and low muscle mass—can I still have kidney disease?

Yes, absolutely. This is an important and often overlooked scenario. Having low creatinine due to low muscle mass doesn’t protect you from kidney disease—it can actually mask it, making diagnosis more challenging. Here’s why: Creatinine levels reflect both muscle mass (how much creatinine is produced) and kidney function (how well creatinine is cleared). If you have both low muscle mass (producing less creatinine) and impaired kidneys (clearing less creatinine), these opposing factors can balance out, resulting in creatinine levels that appear “normal” despite poor kidney function. For example, someone with advanced kidney disease typically has creatinine of 3-4 mg/dL or higher. But if that same person has severe muscle wasting producing very little creatinine, their level might be 1.2 mg/dL—technically “normal” but actually representing significantly impaired kidney function for someone with such low muscle mass. If you have risk factors for kidney disease (diabetes, high blood pressure, family history, previous kidney problems) or symptoms (swelling, changes in urination, fatigue, poor appetite), ask your doctor to assess kidney function using methods less dependent on muscle mass such as cystatin C (another waste product filtered by kidneys but not affected by muscle mass), direct measurement of GFR using special imaging or testing, or urine tests (checking for protein in urine, which indicates kidney damage). Don’t assume low creatinine means your kidneys are fine—request comprehensive kidney function assessment if you have concerns.

8. My doctor says my low creatinine isn’t concerning, but I’m still worried—should I get a second opinion?

It’s completely reasonable to seek clarification or a second opinion if you’re concerned about your health, including low creatinine results. However, first try to have a thorough discussion with your current doctor about why they’re not concerned. Ask specific questions: Why do you think this level is okay for me? What do you think is causing my low creatinine? Are there any tests we should do to make sure there isn’t an underlying problem? Should we monitor it over time to see if it’s stable or declining? Could this be masking kidney disease given my body composition? A good doctor will welcome these questions and provide clear explanations. If after this conversation you still have concerns, especially if you have symptoms (muscle weakness, unexplained weight loss, fatigue, jaundice, etc.), your creatinine is very low (below 0.3-0.4 mg/dL), your levels are declining over time, you have risk factors for serious conditions (liver disease, chronic illness, malnutrition), or your doctor dismisses your concerns without adequate explanation, then seeking a second opinion is appropriate. You might consult a nephrologist (kidney specialist), hepatologist (liver specialist), or endocrinologist depending on your specific situation and suspected causes. Bring all your lab results and medical records to the second opinion appointment. Ultimately, you’re entitled to understand your health status and feel confident in your care. If your current doctor can’t provide that reassurance, seeking another perspective is a responsible health decision.

9. Can stress, lack of sleep, or other lifestyle factors cause low creatinine?

Stress and poor sleep don’t directly cause low creatinine, but they can indirectly contribute to conditions that lower creatinine levels. Here’s how: Chronic stress can lead to poor appetite and inadequate nutrition, potentially causing malnutrition and muscle loss over time. Stress may reduce physical activity and exercise, contributing to muscle atrophy from disuse. Chronic stress contributes to or worsens various health conditions that can affect muscle mass. Stress can disrupt sleep, and poor sleep impairs muscle recovery and growth, potentially affecting muscle mass over time. Additionally, severe psychological stress and certain psychiatric conditions can lead to eating disorders or self-neglect resulting in malnutrition. However, normal day-to-day stress won’t significantly impact creatinine levels. Other lifestyle factors that can contribute include sedentary lifestyle or prolonged inactivity (causes muscle atrophy and lower creatinine), inadequate protein intake over extended periods, excessive alcohol consumption (can damage liver, affect nutrition, and reduce muscle mass), smoking (contributes to chronic diseases that may affect muscle mass), and extreme dieting or calorie restriction (causes muscle loss along with fat loss). Positive lifestyle modifications that can help maintain healthy creatinine levels include regular physical activity, especially resistance training, adequate sleep (7-9 hours for most adults), stress management (meditation, therapy, relaxation techniques), balanced nutrition with adequate protein and calories, and avoiding excessive alcohol and tobacco. While optimizing these factors is important for overall health, if you have significantly low creatinine, you still need medical evaluation to rule out specific medical conditions rather than assuming it’s just lifestyle-related.

10. If I have low creatinine, does that mean I need to drink less water or change my hydration habits?

No, having low creatinine doesn’t mean you should drink less water. In fact, adequate hydration is important for overall health and kidney function. The only scenario where excessive fluid intake contributes to low creatinine is extreme overhydration that dilutes blood concentration—this is relatively uncommon and occurs when people drink enormous amounts of water (several gallons daily), have psychogenic polydipsia (compulsive water drinking, a psychiatric condition), or deliberately overhydrate for medical tests or drug screening. For the vast majority of people with low creatinine, hydration status isn’t the cause. The low creatinine more likely results from low muscle mass, malnutrition, liver disease, or other factors discussed throughout this article. Normal hydration recommendations still apply: Drink when thirsty and maintain light yellow or pale straw-colored urine. Most people need about 8-10 cups (64-80 ounces) of fluid daily from all sources, though individual needs vary based on climate, activity level, and health status. Adequate hydration is particularly important if you have kidney concerns (even if your creatinine is low) because it helps kidneys function properly. The only situation where you might need to monitor fluid intake more carefully is if you have severe liver disease with ascites (fluid accumulation) or certain heart or kidney conditions where fluid restriction is medically necessary—but your doctor would specifically advise you about this. Bottom line: Don’t change your hydration habits based on low creatinine alone. Drink adequate fluids for your health needs and focus on addressing the actual cause of your low creatinine through appropriate medical evaluation and treatment.